Peertracks: A Bitsapphire Case Study on Digital Copyrights and Media Platforms in Blockchain

Blockchain Solutions for Artists

The following case study will examine the history of file sharing, media platforms, and the blockchain decentralized application (dApp) that Bitsapphire developed for Peertracks. This dApp answers the following questions:

Why are artists not paid a more significant share of the profits from their work & how has this continued to happen for so long?

We have accumulated business model data regarding the most popular media platforms in 2018. We will compare that data with Peertracks’ business model, and briefly discuss the effects of file sharing in music sales. This will help us determine where the money flows.

By examining the steps we follow while providing blockchain consulting and development for Peertracks, we will attempt to provide a picture of what creates a healthy token economy.

A Brief History of Peer-to-Peer Technology

Peer-to-peer technology can be viewed as a “predecessor” to blockchain technology. It served as a decentralized technology with no central power; essentially blockchain but with far less security.

Peer-to-peer technology was the original intention of the Internet. Historically, ARPANET connected four prominent universities, UCLA, University of Utah, Stanford Research Institute, and UC Santa Barbara in a peer-to-peer method. Servers acted as clients and clients acted as servers.[1]University of Florida – p2p networking

Although this technology was a proto-P2P, the first available system to use it was Usenet, a bulletin board system that categorized items into what it called newsgroups.[2]The Social Forces Behind the Development of Usenet – Michael Hauben Usenet acted as a worldwide system decades before the actual world wide web (WWW) came into existence. It is credited with incredible cultural influence, including popularizing terms such as FAQ, flame, spam, etc.[3]NewsDemon – Usenet Newsgroups Terms Defined – Spam

During the 1990s, companies started adopting this technology for private use to cut losses, due to the faster throughputs it provided. The biggest adoption was Napster and its worldwide success.

Copyrights and File Sharing

Napster was founded by two college students, Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker. Both students saw an opportunity for people to share their MP3 files in a peer-to-peer environment. Napster became a big success and haven for music enthusiasts to find and share music, amassing 80 million registered users at the peak of its operations.[4]Requiem for Napster – Michael Gowan

The website was up and running for a very short time. After just 1 year of operation, Napster encountered issues with large corporations due to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act [7]The Digital Millennium Copyright Act Of 1998 U.S. Copyright Office Summary (DMCA). Musical recording companies (Sony, A&M, Interscope, etc.) and popular artists/bands such as Metallica began suing Napster for directly violating the DMCA.[5]A & M RECORDS, INC. v. Napster, Inc., 114 F. Supp. 2d 896 (N.D. Cal. 2000) – U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California – August 10, 2000 [6]United States District Court – Northern District of California – Metallica and Dr.Dre vs. Napter

After the fall of Napster, many other peer-to-peer sites appeared, including Gnutella, Freenet, Kazaa, BearShare, etc.

The Cost of File Sharing and the Era of Media Platforms

Although piracy is often vilified as one of the main reasons artists don’t make as much money as they should, a large list of surveys and studies completed on the topic show otherwise.

The two studies below are showcased in order to attain a more valid reason as to why artists typically receive such a small cut of the profits from their work. From here, we can see how Bitsapphire’s practices in blockchain came into an application.

Studies presented:

- The Effect of File Sharing on Record Sales: An Empirical Analysis – Revisited – F. Oberholzer-Gee, Koleman Strumpf [8]Oberholzer-Gee,Felix, and Koleman Strumpf. “The effect of file sharing on record sales, revisited.” Information Economics and Policy 37 (2016): 61-66.

- Estimating Displacement Rates of Copyrighted Content in the EU – An unpublished study [9]Martin van der Ende, Joost Poort, Robert Haffner, Patrick de Bas, Anastasia Yagafarova, Sophie Rohlfs, Harry van Til – May – 2015 – “Estimating displacement rates of copyrighted content in the EU.”

- The Effect of File Sharing on Record Sales: An Empirical Analysis – Revisited

The Oberholzer-Gee and Strumpf study used data from German and U.S. students. The data was put through rigorous testing to reach a number of conclusions. It is important to note, that studies are almost always dependent on their approach, a product-level approach and a person-focused design will each result in a different set of conclusions.

The product-level approach found little to no displacement between the two facts.

Studies that rely on a person-specific approach yield negative effects, some studies even attribute the loss of revenue completely to illegal downloading.

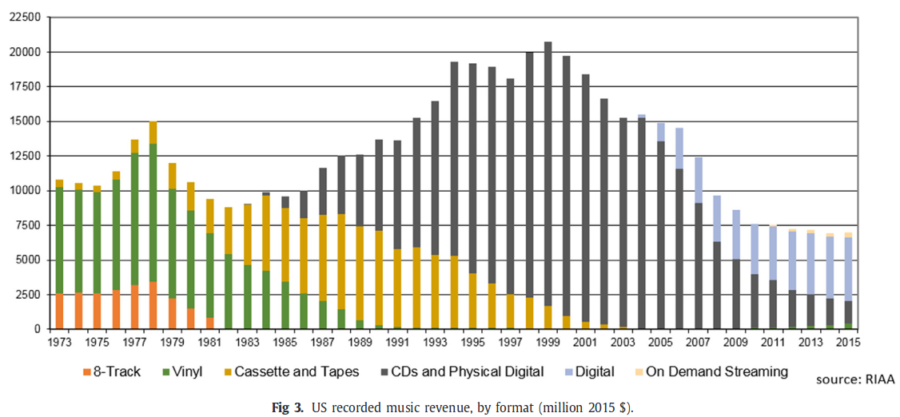

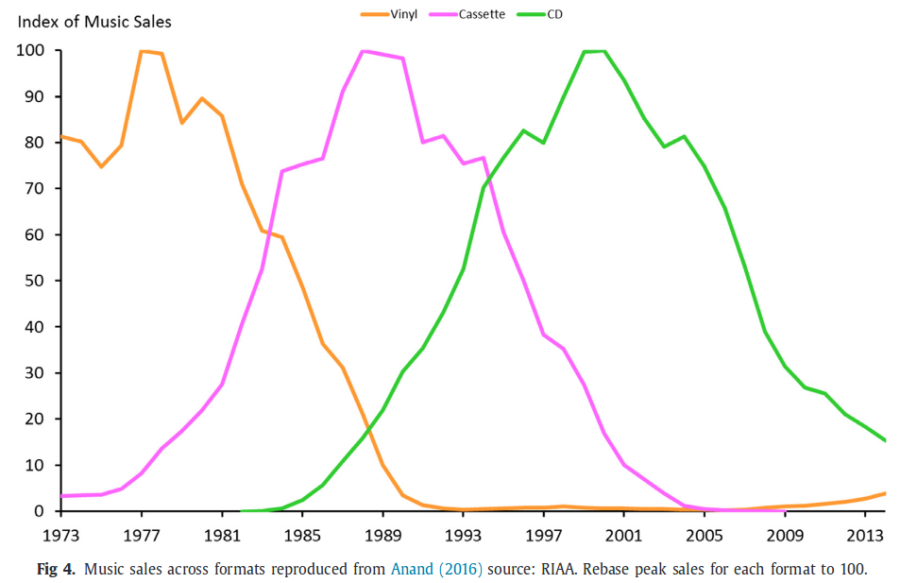

By examining the following two graphs, we can draw some conclusions.

Although the 2000s were a boom period for file sharing, including Napster giving birth to many other clients, we can see that this time period did not experience a major drop off in revenue. While the 90s experienced a baffling 75% increase in revenue over a single decade. Meanwhile, the previous two decades remained reasonably stable. This relates to our next point on the importance of format changes in technology.

By looking at the technology formats used on a graph, we can come to another conclusion: declines in sales aren’t a millennial issue. As we can tell from Figure 1, the late 70s and early 80s bear a striking resemblance to the early 2000s. We can see that sales experienced a similar sharp increase before rapidly declining.

These peaks and valleys can be attributed to a change in standard formats. The delay in demand is one factor, as customers transition from the old to the new format. Secondly, repurchasing of owned music for the new format contributes to a peak in sales. The second factor only occurs when the technology has become familiar and well established.

Another factor in the decline of sales during the 2000s is the transition between two formats in a rapid period. Buyers don’t want to spend their money if the purchased format is going to become obsolete quickly.

The study ends in 2015. 2016 and 2017 were the first time since 1999 that US music revenue grew for two years in a row.[10]Recording Industry Association of America “News and Notes on 2017 RIAA Revenue Statistics.” This leads us back to our previous conclusion that people slowly become more familiar with formats, and in-term, sales increase.

However, this study fails to utilize a proper tool for the measurement of piracy costs on a more diverse set of fields. This would give us much more approximate percentages. These piracy costs are examined in our next study.

Estimating Displacement Rates of Copyrighted Content in the EU To save time, I suggest reading the full study, as it clearly outlines the tools used to come to these conclusions. This is an unpublished study that had an investment of $443,000 USD from the EU. The study reached these interesting conclusions:

Piracy causes a 4.4% average decrease in blockbuster movie sales.

In some areas, such as gaming, pirating actually had positive effects, leading to more purchases.

No conclusions were reached regarding the impact of piracy on music sales.

Media Platforms in the 21st Century

Now that we have reached a conclusion regarding piracy, we will begin building an argument using data accumulated in 2018 from the nine most popular online music streaming services, free or paid. This will allow us to determine what these issues are and how Peertrack’s and Bitsapphire’s applied blockchain technology can tackle them.

The nine most popular music streaming services are:

- Napster

- Tidal

- Apple Music

- Google Play Music

- Deezer

- Spotify

- Amazon

- Pandora Premium

- Youtube

| Name | Average price paid per stream | Total users (millions) | Signed plays needed to earn minimum wage | Average streams per song | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Napster | 0.019 | 5 | 77,474 | 32 | |

| Tidal | 0.0125 | 4.2 | 117,760 | 49 | |

| Apple Music | 0.0125 | 4.2 | 117,760 | 49 | |

| Google Play Music | 0.00676 | 10 | 217,751 | 90 | Google Play users is an estimate |

| Deezer | 0.0064 | 16 | 230,000 | 95 | |

| Spotify | 0.00437 | 159 | 336,842 | 139 | |

| Amazon | 0.00402 | 20 | 366,169 | 151 | |

| Pandora Premium | 0.00133 | 81 | 1,106,767 | 456 | Pandora has 81 million active but unpaid users |

| Youtube | 0.00069 | 1,002 | 2,133,333 | 876 |

We will use a set of data from the website “Information is Beautiful”. This list has a great deal of information regarding these streaming services, and more specifically, their payment systems.

The information extracted can be found here: Money Too Tight to Mention? Major Music Streaming Services Compared. All credits go to Information is Beautiful.

The payments aren’t low considering an accomplished artist can attain millions of views relatively easily. The problem is that artists are hit with a combination of price cuts from both recording labels and streaming services.

In a 2015 interview the lead singer of the Talking Heads, David Byrne, said that he considers the most substantial problem in the music industry to be a lack of transparency.

Prominent artists don’t mind the current system because it benefits them. They already have large advertising budgets, so their songs receive more views and a larger share of the profits. The issue stands with newer artists. These artists have to choose between making the music they like or producing what will appeal commercially.

The three major labels own a large portion of all of the music from the past few decades, making streaming service platforms more of a secondary option for artists.

The three largest companies: Sony, Universal, and Warner, all require non-disclosure agreements in their contracts. To explain what this means for artists, Byrne created a hypothetical example:

“Let’s say in January Sam Smith’s “Stay With Me” accounted for 5 percent of the total revenue that Spotify paid to Universal Music for its catalog. Universal is not obligated to take the gross revenue it received and assign that same 5 percent to Sam Smith’s account. They might give him 3 percent — or 10 percent. What’s to stop them?”

Labels will also typically withhold data from three other income sources: Streaming service advances, streaming service equity, and catalog service payments for old songs. Artists are only receiving a small percentage of the profits from songs they have created.

If artists had access to all of this information and data, such as which fans or audiences are generating more income, they could leverage that information to expand their reach and bring in more revenue. This would benefit both the artists and the labels.

For more insight and ideas, read Byrne’s full interview with the New York Times here

Peertracks and the Blockchain Solution

In order to discuss Peertracks we also have to elaborate on MUSE, a transparent blockchain system that uses Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPOS) to verify blocks. The case study regarding Peertracks and MUSE is going to be on a purely architectural level .

Trust in the Peertracks Environment

Due to the way the blockchain and MUSE are built, there is no central government/entity. This raises the question: How can a user manage to trust a contract enough to purchase its tokens?

To solve this issue, the system utilizes a ranking method which emphasizes not only users but their smart contracts as well. This ranking system uses your connections and their MUSE Vesting score to calculate the legitimacy of an artist. This allows users to whitelist specific artists that they know are legitimate.

This process creates a graph with a score. That graph allows platforms with MUSE as their base blockchain to have criteria over songs that appear in that platform.

The Witness Blockchain – DPOS Explained

MUSE as the default Peertracks blockchain uses a different type of consensus mechanism. Using DPOS, Daniel Larimer created this blockchain consensus method. Daniel Larimer also developed Graphene, the Bitshares toolkit which MUSE uses.

DPOS prevents the need for centralization by using witnesses. These witnesses sign blocks in the system for validation. The witnesses are voted on by the users in a democratic fashion, by casting votes in their transaction. This process ensures that adequate witnesses will be chosen.

The system itself has defenses to prevent malicious witnesses. By not signing blocks, witnesses may get voted out, losing future profits. A witness will only refuse to sign if he or she has something to profit from. Fortunately, the witnesses are unable to sign invalid blocks. Blocks cannot be signed as valid unless they have been attached to a user.

This system of witnesses and users is quite robust. First, it gives people the incentive to adhere to a list of rules in order to become or maintain a position as a witness. Secondly, when the blocks are signed, they are immediately processed. This is in sharp contrast to Bitcoin’s Proof-of-Work, because of how the system utilizes Merkle Trees[11]Merkle Trees – US patent 4309569 – Ralph Merkle, “Method of providing digital signatures” and Hashcash[12]Hashcash Proof-of-Work – March 1997. A bundle of transactions has to be made before they can be verified and confirmed.

These attributes make MUSE faster and more efficient at handling transactions and create a much healthier token economy.

The MUSE Contract

When you place your music on MUSE, you’re putting it on a Smart Contract designed to produce a database for music metadata, transparency, and low friction. The contract also offers two features:

- Licensing Conditions – These can be displayed publicly to everyone, and will give users the freedom to pay the necessary conditions to use your music.

- Royalty Splitting – This allows a creator to split the earnings to different people.

Regarding how useful the service is, Peertracks does not charge any transaction fees for daily operations, such as receiving or sending your funds or updating your contract. Everything that is front-side is handled in the browser, so there is no need to download clients or apps. Registration is immediate, and you don’t need to purchase anything or provide credit card information.

Peertracks and MUSE Features

Peertracks offers other features that open up many new entrepreneurial opportunities for artists.

User Issued Assets (UIA) make it possible for anyone to create their own token within the system. Artists can launch an “ICO” if they have don’t have the necessary funds, and if the song/album becomes a success, both sides of the party will be happy.

Muse also offers a decentralized exchange (DEX) for trading Muse assets, MUSE dollars, or any other UIA. Any token can be traded. This enables trades between investors, or simply artists sharing tokens.

Conclusions

Piracy is not the primary reason for artists receiving low percentages of the profit produced from their art. Instead, it is one issue among much larger problems within the music industry.

In actuality, the core issue is the lack of transparency regarding where and how funds flow from initial profit. Artists are unable to keep track of true profit statistics and platforms aren’t legally allowed to share data.

Peertracks has managed to create a blockchain solution for the issues that afflict the music industry. Through just the simple act of transparency, many problems simply fix themselves.

The blockchain solution includes features that can make it much easier for artists to earn money from their songs. By offering investment opportunities such as UIAs, exchanging tokens, or splitting royalties, Peertracks and Bitsapphire have developed a token economy that enables artists to be entrepreneurs and not just creators.

The MUSE Blockchain was not developed for a single use, e.g. Peertracks. It’s tools and features allow anyone to create a transparent streaming platform through it’s smart contract capabilities.